Most people with diabetes rely on insulin to survive. But for a small number, the very thing keeping them alive can trigger a dangerous reaction. Insulin allergies are rare - affecting about 2.1% of users - but they’re serious enough to warrant immediate attention. If you’ve ever noticed swelling, itching, or redness right after an injection, or worse, trouble breathing or a sudden drop in blood pressure, you’re not imagining it. This isn’t just a side effect. It’s an immune response, and it needs to be handled differently than a bad injection technique or a bruise.

What Does an Insulin Allergy Actually Look Like?

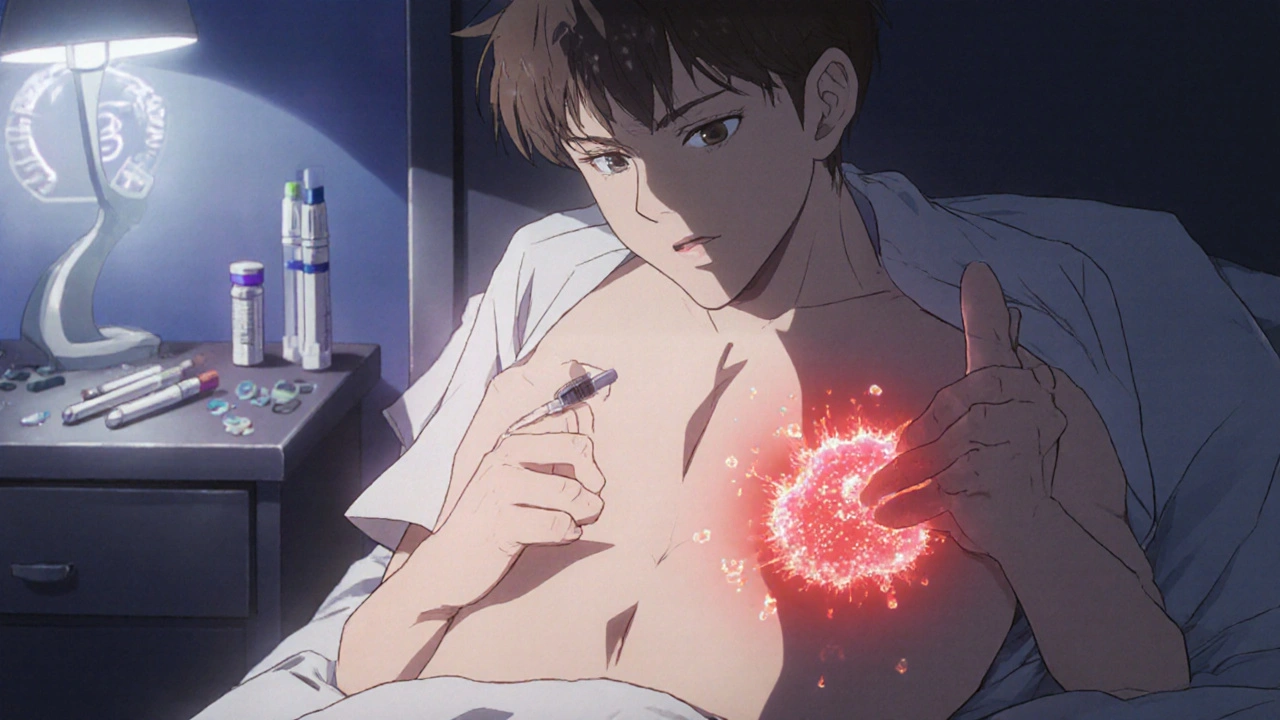

Not all reactions are the same. Most are local - meaning they stay right where you injected the insulin. You might see a red, itchy bump that swells up within 30 minutes to six hours. It can feel tender, like a small knot under the skin. These usually fade within 24 to 48 hours and happen in about 2-3% of people using older forms of insulin. But here’s the catch: even if you’ve been on the same insulin for years, you can suddenly develop these reactions. One patient reported joint pain and swelling after 12 years of stable insulin use. That’s not uncommon.

Then there are the systemic reactions. These are rare - less than 0.1% of users - but life-threatening. Symptoms include hives all over the body, swelling of the lips, tongue, or throat, difficulty breathing, dizziness, or a sudden drop in blood pressure. This is anaphylaxis. If you feel your airway closing or your chest tightening, call emergency services immediately. Don’t wait. Don’t drive yourself. These reactions can escalate in minutes.

There’s also a third type: delayed reactions. These show up hours or even days later. Think bruising, joint pain, or a rash that doesn’t go away for weeks. These aren’t caused by IgE antibodies like immediate reactions. They’re T-cell mediated - a different part of the immune system. That means they need a different treatment approach.

Is It Really the Insulin? Or Something Else?

Many assume the insulin molecule itself is the problem. But in many cases, it’s not. Modern insulins are highly purified. The real culprits are often the additives: preservatives like metacresol or zinc, or stabilizers used to keep the insulin stable in the pen or vial. For example, Humalog has higher levels of metacresol than other brands. If you react to one insulin but not another, switching brands might solve the problem - not because the insulin is different, but because the excipients are.

Doctors can test for this. Skin prick tests or intradermal tests can pinpoint whether your body is reacting to insulin itself or one of the additives. These aren’t routine, but if you’ve had more than one reaction, your diabetes team should refer you to an allergist. Don’t assume it’s just irritation. Getting the right diagnosis changes everything.

What Should You Do If You React?

First: don’t stop insulin. That’s the biggest mistake people make. Skipping doses because you’re scared of a reaction can lead to diabetic ketoacidosis - a medical emergency that’s far more dangerous than most allergic reactions. Contact your diabetes care team right away. They’ll help you figure out the next steps without putting your blood sugar at risk.

For mild, localized reactions, over-the-counter antihistamines like cetirizine or loratadine can help reduce itching and swelling. Applying a topical calcineurin inhibitor - like tacrolimus or pimecrolimus - right after injection and again 4-6 hours later can suppress the immune response at the site. For delayed, stubborn rashes, a mid-to-high potency steroid cream like flunisolide 0.05% applied twice daily for a few days often clears it up.

If you’ve had a systemic reaction, you’ll need a full allergy work-up. That includes blood tests for specific IgE antibodies and possibly skin testing with different insulin formulations. In some cases, allergists will recommend immunotherapy - slowly introducing tiny, increasing doses of insulin under close supervision. Studies show this works in about two-thirds of patients. One study followed four patients; three saw complete or near-complete symptom resolution after months of controlled exposure.

Switching Insulin Types: A Common and Effective Solution

Here’s the good news: in about 70% of cases, simply switching to a different insulin brand or type resolves the issue. That could mean going from human insulin to a newer analog like glargine, degludec, or lispro - each has a slightly different molecular structure and different excipients. If you were on a pork-derived insulin in the past, switching to recombinant human insulin alone often eliminates the problem.

Some newer insulins are designed with fewer additives. For example, certain basal insulins use different preservatives or none at all. Your doctor can check the ingredient list of your current insulin and compare it to alternatives. You might be surprised how small changes - like switching from a vial to a pen, or from one manufacturer to another - make a huge difference.

But don’t switch blindly. Work with your team. Some insulins are only available in certain forms (pen vs. vial), and some aren’t approved for your type of diabetes. Type 1 patients have fewer options than Type 2. But even within those limits, there’s often a viable alternative.

When Nothing Seems to Work

For the 30% of patients who don’t respond to switching or immunotherapy, things get trickier. In some cases, especially with Type 2 diabetes, doctors may consider switching to oral medications - like GLP-1 agonists or SGLT2 inhibitors - if blood sugar control allows. But for Type 1 patients, insulin is non-negotiable. That’s where specialized care comes in.

Some clinics now use continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) during desensitization. This lets them adjust insulin doses in real time to avoid dangerous lows while slowly building tolerance. It’s not widely available, but it’s becoming more common in major diabetes centers. The goal isn’t to cure the allergy - it’s to let you safely use insulin again.

There’s also emerging research into insulin formulations with reduced immunogenicity. Companies are experimenting with new delivery systems and preservative-free versions. While these aren’t mainstream yet, they offer hope for the future.

What to Track and When to Call for Help

Keep a detailed log. Note the date, time, insulin brand, dose, injection site, and symptoms - including how long they lasted and how severe they were. Did the reaction happen only after a new batch? Did it happen with every injection or just some? Did it improve after changing sites? This data is gold for your allergist.

Call 999 (or your local emergency number) immediately if you have:

- Swelling of the lips, tongue, or throat

- Difficulty breathing or wheezing

- Dizziness, fainting, or rapid heartbeat

- Sudden skin discoloration or cold, clammy skin

For anything less severe - but still concerning - call your diabetes team within 24 hours. Don’t wait for it to get worse. Early intervention prevents complications.

Final Thought: You’re Not Alone

Insulin allergies are rare, but they’re real. And they’re manageable. You don’t have to choose between your health and your life-saving medication. With the right team - your endocrinologist, your allergist, and your diabetes educator - you can find a solution. Whether it’s a different insulin, a topical treatment, or a carefully monitored desensitization plan, there’s a path forward. The key is acting fast, documenting everything, and never stopping insulin without professional guidance. Your body is fighting a battle you didn’t ask for. But with the right tools, you can win it.

Can you develop an insulin allergy after years of using it without problems?

Yes. While most insulin allergies appear soon after starting treatment, delayed hypersensitivity reactions can occur even after 10 or more years of stable use. These are often T-cell mediated and may present as joint pain, bruising, or persistent rashes rather than immediate swelling or hives. Changing insulin brands or excipients can sometimes trigger a reaction in someone who previously tolerated the same insulin for years.

Is an insulin allergy the same as an insulin side effect?

No. Common side effects like sweating, shaking, or anxiety are signs of low blood sugar - not an immune response. True insulin allergies involve the immune system reacting to the insulin molecule or its additives, causing symptoms like hives, swelling, or breathing problems. If you’re unsure whether your symptoms are an allergy or a blood sugar issue, check your glucose level. If it’s normal and you still have symptoms, it’s likely an allergic reaction.

Can antihistamines treat an insulin allergy?

Antihistamines can help manage mild, localized symptoms like itching or redness. But they won’t stop a systemic reaction like anaphylaxis. For severe reactions, epinephrine is the only effective treatment. Antihistamines are a supportive tool, not a solution. Always have a plan with your doctor for what to do if symptoms worsen.

Is insulin desensitization safe?

Yes, when done under medical supervision. Desensitization involves gradually increasing doses of insulin in a controlled setting, often using a CGM to monitor blood sugar. Studies show it resolves symptoms completely in about two-thirds of patients. While it requires time and careful monitoring, it’s one of the most effective long-term solutions for people who can’t switch insulin types.

Can I use a different injection site to avoid reactions?

Rotating injection sites is always recommended to prevent lipohypertrophy, but it won’t prevent an allergic reaction. If your body is reacting to the insulin or its additives, the immune response will happen regardless of where you inject. However, if you’re developing localized nodules, changing sites can help reduce irritation and give the tissue time to heal while you work with your doctor on a longer-term solution.

Should I carry an epinephrine auto-injector if I have an insulin allergy?

If you’ve ever had a systemic reaction - such as swelling in the throat, difficulty breathing, or dizziness - your doctor should prescribe an epinephrine auto-injector. Even if your reactions have been mild so far, the risk of a future severe reaction is real. Carry it with you at all times, and make sure those around you know how to use it. Don’t wait for a crisis to prepare.

Are newer insulins less likely to cause allergies?

Yes. Modern recombinant human insulins and analogs are much purer than the animal-sourced insulins used in the 1930s, when up to 15% of users had allergic reactions. Today’s formulations have fewer impurities and better-controlled excipients. While allergies still happen, the incidence is far lower - around 2.1%. Newer insulins with modified preservatives or preservative-free options are also being developed specifically to reduce immune triggers.