Medication Shortage Substitution Calculator

This calculator helps healthcare providers determine equivalent doses when substituting medications during shortages. Always consult clinical guidelines and protocols before changing doses.

Important: Substitution ratios are approximate. Actual dosing depends on patient factors, clinical context, and manufacturer specifications. Errors can be fatal. This tool is for reference only.

Equivalent Dose Calculation

When your hospital runs out of morphine, or the IV antibiotics you rely on for infections disappear from the shelf, it’s not just an inconvenience-it’s a crisis. Medication shortages aren’t rare glitches anymore. They’re a daily reality in hospitals, clinics, and even some pharmacies across the U.S. and beyond. In 2022, the FDA recorded 287 drug shortages, affecting nearly one in five essential medications used in hospitals. And it’s not getting better. The average shortage now lasts almost 10 months. For cancer drugs, it’s over 14 months. This isn’t a future problem. It’s happening right now.

Why Are These Shortages Happening?

Most shortages don’t come from a lack of demand. They come from broken manufacturing. Over 46% of all drug shortages in 2022 were caused by quality issues at production facilities-contaminated batches, equipment failures, or failure to meet FDA standards. These aren’t small mistakes. They’re systemic failures in factories that make generic sterile injectables: the life-saving drugs like morphine, saline, antibiotics, and chemotherapy agents. These drugs are made by just three companies that control 75% of the market. If one plant shuts down, the entire country feels it.

There’s also the global supply chain. Eighty percent of the active ingredients in U.S. drugs come from overseas-mostly China and India. A single flood, political disruption, or export ban in one country can ripple across the entire system. And when manufacturers can’t raise prices to cover the cost of better quality control-because Medicare and Medicaid rebates lock them into low reimbursement rates-they cut corners instead.

Who Gets Hit the Hardest?

It’s not evenly distributed. Rural hospitals, safety-net clinics, and facilities serving Medicaid or uninsured patients are hit hardest. A 2023 study by the American College of Physicians found that 78% of these facilities had to cancel or delay procedures because they couldn’t get the drugs they needed. Nurses in these places often wait hours longer to give critical meds. Patients get less pain relief. Cancer treatments get postponed. In some cases, people die because the right drug wasn’t there.

Even in big city hospitals, the stress is real. Pharmacy teams work 12+ extra hours a week just to find alternatives. Pharmacists scramble to switch morphine to hydromorphone, a different opioid that requires new dosing protocols. One pharmacist on Reddit reported a 15% spike in medication errors during that switch. Nurses report 22-minute delays in giving time-sensitive meds. Doctors are forced to make decisions based on what’s in stock-not what’s best for the patient.

What Can Hospitals and Pharmacies Do?

Waiting for a shortage to be announced is too late. By then, the supply is already gone, and the chaos has begun. The most effective hospitals act before the FDA even posts the alert. They set up a shortage management committee-a small team with real authority. It includes pharmacists, nurses, IT staff, risk managers, and finance officers. They meet weekly. When a shortage hits, they meet within four hours.

This team tracks everything: when the shortage was first noticed, what alternatives were considered, how it affected patient care, and whether any errors occurred. They keep a log. Not just notes. A real, searchable database. Hospitals that do this see 33% fewer medication errors during shortages.

They also build buffer stock. ASHP recommends keeping 14 to 30 days’ supply of critical drugs. But money is tight. Most safety-net hospitals can only afford 8 to 12 days. That’s not enough. The gap is real. And it’s deadly.

What Are the Alternatives?

Not every drug has a direct substitute. But many do. The key is knowing them in advance.

- Morphine shortage? Hydromorphone is often used-but it’s five to seven times more potent. Dosing must be recalculated. Nurses need training. Monitoring increases.

- Vancomycin out? Linezolid or daptomycin can work for certain infections, but they’re more expensive and require different monitoring.

- IV saline running low? Some hospitals use oral rehydration for stable patients. Others switch to lactated Ringer’s-but that’s not always available either.

Switching drugs isn’t simple. It requires clinical judgment, updated protocols, staff training, and electronic health record changes. That’s why simulation drills matter. Hospitals that run quarterly mock shortages-where teams practice switching meds, communicating with providers, and documenting errors-handle real events far better.

Why Isn’t the Government Fixing This?

The U.S. relies on voluntary reporting. Manufacturers are asked-not required-to tell the FDA when a shortage is coming. Only 65% comply. Meanwhile, countries like France and Canada have mandatory reporting. When a plant in France can’t meet demand, the government steps in within days. Shortages there last 37% less time.

Germany keeps strategic stockpiles of critical drugs. During the pandemic, they had enough IV fluids and antibiotics to last through the worst months. The U.S. has the Strategic National Stockpile-but it’s meant for bioterrorism or natural disasters, not routine drug failures. It doesn’t hold morphine, saline, or chemo drugs.

There’s also the money problem. Generic drug makers can’t raise prices to fix their factories because Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements are frozen. The 340B program, meant to help safety-net hospitals, actually makes it harder for manufacturers to earn enough to invest in quality. The American Medical Association says this is a policy failure, not a supply issue.

What’s Changing?

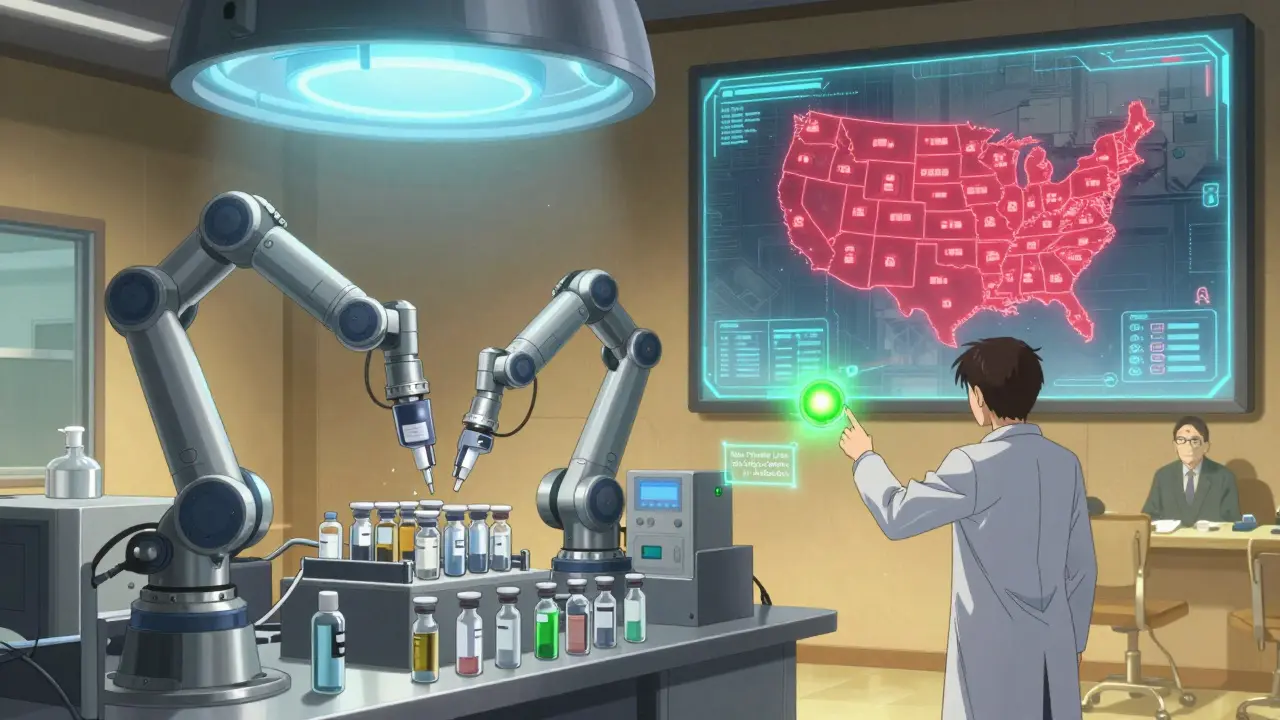

There are signs of progress. In 2022, the Department of Health and Human Services created a new role: Supply Chain Resilience and Shortage Coordinator. They’ve built a response framework and are pushing for better data sharing. The FDA’s draft guidance on risk management plans-expected to be finalized in mid-2024-could force manufacturers to map their supply chains and show how they’ll prevent shortages.

Some experts are pushing for advanced manufacturing tech-like modular, flexible production lines that can switch between drugs in hours instead of weeks. If just half of U.S. facilities adopted this, shortages could drop by 40%.

And then there’s reimbursement. The American College of Physicians wants Medicare to reward reliable manufacturers. If a company consistently delivers high-quality drugs on time, they get a small bonus. That could unlock $1.5 billion in new investment.

But without policy change, the trend is clear: shortages will grow 8-12% every year through 2030. Oncology, anesthesia, and critical care drugs will be worst hit.

What Can You Do?

If you’re a patient: Ask your doctor or pharmacist what alternatives exist if your drug runs out. Don’t assume the next one will be the same. Know your meds. Keep a list.

If you’re a provider: Start a shortage log. Train your team. Practice the switch. Don’t wait for the FDA email.

If you’re in policy or administration: Push for mandatory reporting. Fund buffer stockpiles. Reform reimbursement. This isn’t just a pharmacy problem. It’s a public health emergency.

Medication shortages aren’t going away. But they’re not inevitable. They’re the result of choices-about money, regulation, and priorities. The system is broken. But it can be fixed. Not with magic. Not with hope. With planning. With action. With the will to make it right.