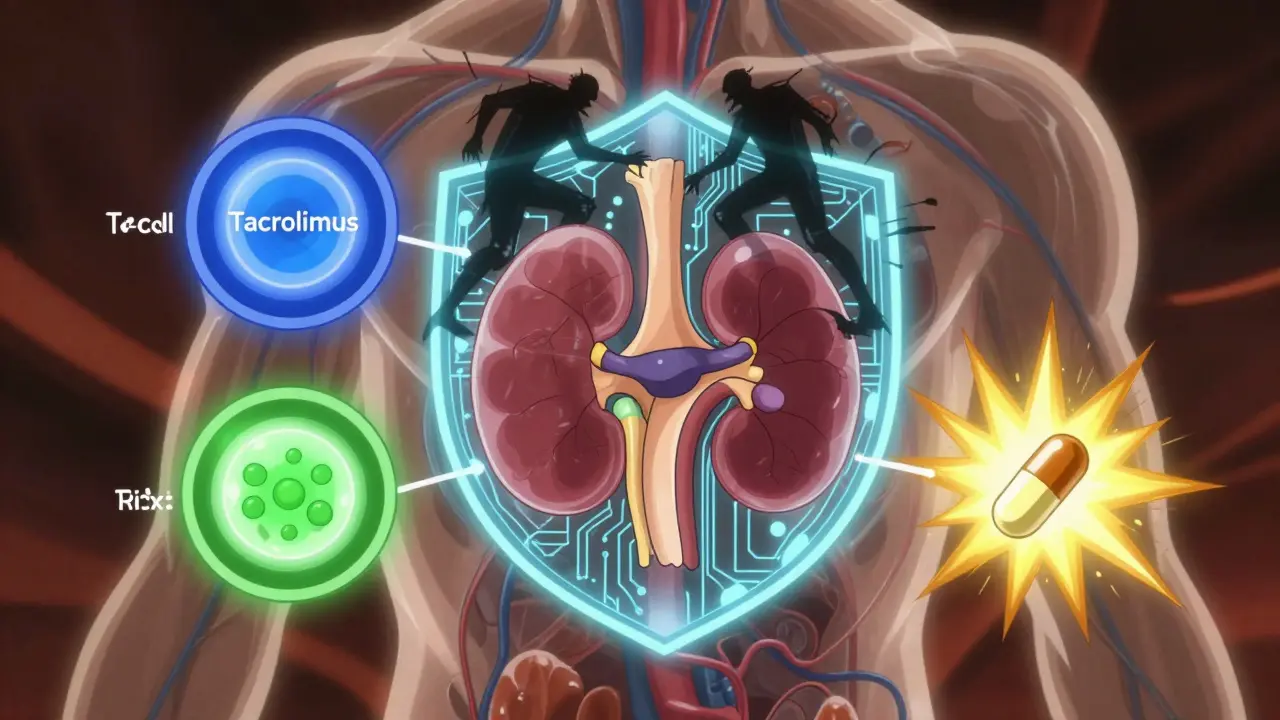

After a kidney transplant, your body doesn’t know the new organ isn’t a threat. It sees it as an invader and tries to attack it. That’s where tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids come in. These three drugs form the backbone of immunosuppression for most kidney transplant patients today. They don’t just prevent rejection-they keep your new kidney alive long-term. But they’re not magic pills. They come with side effects, strict dosing rules, and lifelong monitoring. Understanding how they work-and how they don’t-is key to surviving and thriving after transplant.

Why This Three-Drug Combo Is the Gold Standard

Since the mid-1990s, the combination of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and corticosteroids has become the most common immunosuppression plan for kidney transplant recipients. Before this, doctors relied on cyclosporine, which had high rejection rates and nasty side effects like shaky hands and swollen gums. Tacrolimus changed the game. It was stronger, more predictable, and didn’t cause as many cosmetic problems. Mycophenolate added another layer of protection, and steroids gave a quick, powerful punch right after surgery. The numbers don’t lie. One major study showed that when patients got all three drugs, only 8.2% had biopsy-proven acute rejection in the first year. When they skipped mycophenolate and used just tacrolimus and steroids? That number jumped to 21%. That’s a 61% drop in rejection just by adding one drug. That’s why this combo became the default. Today, about 90% of U.S. transplant centers use some version of this triple therapy. It’s not perfect-but it’s the best we’ve got for now.Tacrolimus: The Heavy Hitter

Tacrolimus (also called FK506) is a calcineurin inhibitor. It blocks the signal that tells your T-cells to attack the new kidney. Think of it like cutting the phone line between your immune system and the organ. It works fast-within 12 to 24 hours-and you need to take it twice a day, usually in the morning and evening. But here’s the catch: tacrolimus has a very narrow window. Too little, and your body rejects the kidney. Too much, and you risk kidney damage, nerve problems, or even diabetes. That’s why doctors track your blood levels closely. In the first year after transplant, your target range is usually between 5 and 10 nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL). After that, it often drops to 3-7 ng/mL to reduce long-term toxicity. The drug is absorbed in your gut, but not always the same way every time. Food, stomach acid, and other medications can mess with absorption. That’s why you’re told to take it on an empty stomach or always with the same kind of meal. Some patients get diarrhea or headaches. Others develop tremors or trouble sleeping. And yes-about 18-21% of people end up with new-onset diabetes after transplant, mostly because tacrolimus messes with insulin production.Mycophenolate: The Silent Protector

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is a prodrug that turns into mycophenolic acid (MPA) in your body. It doesn’t kill immune cells. Instead, it stops them from multiplying. It’s like putting a lock on the factory that makes new attack cells. You take it as a pill, usually 1 gram twice a day. That’s two pills in the morning, two at night. But here’s the problem: up to 30% of patients can’t handle it. Diarrhea is the #1 reason people stop taking it. Nausea, vomiting, and stomach cramps are common. Some get low white blood cell counts (leukopenia), which makes them more prone to infections. About 15% of patients need to reduce their dose or quit altogether because of these side effects. Doctors now know that just looking at your blood level at one point (called a trough level) isn’t enough. The real magic is in the AUC-the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over 12 hours. Some centers are starting to use AUC monitoring to fine-tune doses, especially for patients who keep having rejection episodes or side effects. If your MPA levels are too low, rejection risk goes up. Too high? You get more side effects. It’s a tightrope walk.Steroids: Fast, Powerful, But Problematic

Corticosteroids like methylprednisolone and prednisone are the first responders. Right in the operating room, you get a 1,000-mg IV dose. That’s a massive shot to calm your immune system immediately after surgery. Then, over the next few weeks, your dose gets lowered-fast. By 3 to 4 weeks, you’re down to 15 mg a day. By 2 to 3 months, it’s usually 10 mg. Steroids are brutal on the body. Weight gain, especially around the face and belly. Acne. Mood swings. Trouble sleeping. Thinning skin. Easy bruising. And for some, high blood pressure and bone loss. That’s why doctors want to get you off them as soon as possible. Here’s the twist: studies show you don’t always need them. In a 2005 trial, patients who skipped steroids entirely but got a special induction drug (daclizumab) plus tacrolimus and MMF had the same rejection rates as those on the full triple therapy. And guess what? They felt better. Less weight gain. Fewer mood crashes. Better skin. About 89% stayed steroid-free after six months. So why do we still use steroids? Because they’re cheap, widely available, and work in emergencies. If you start rejecting the kidney, a quick steroid pulse can often stop it in its tracks. But for many patients, the long-term downsides outweigh the benefits.What Goes Wrong? Side Effects and Risks

No one talks enough about how hard this regimen is to live with. You’re not just taking pills-you’re managing a whole new set of health problems. - Diabetes: 1 in 5 transplant patients develop it because of tacrolimus. You’ll need to check your blood sugar, watch your carbs, and maybe start insulin. - Infections: Your immune system is turned down. You’re more likely to get colds, flu, urinary infections, and even serious ones like CMV (cytomegalovirus). Some patients need antiviral pills for months after transplant. - GI trouble: Diarrhea from MMF is so common, many patients carry emergency meds or change their diet completely. - Kidney damage: Ironically, the drugs meant to save your new kidney can slowly harm it. Tacrolimus is especially tough on kidney tissue over time. - Cancer risk: All immunosuppressants carry a black box warning for skin cancer and lymphoma. You need regular skin checks and to avoid sunburns at all costs. And here’s the kicker: even with all this, 25% of adult kidney transplant patients lose their graft and go back on dialysis within five years. That’s not failure-it’s the reality. The drugs prevent rejection, but they don’t stop chronic injury. The kidney slowly wears out, even if it’s not being attacked.

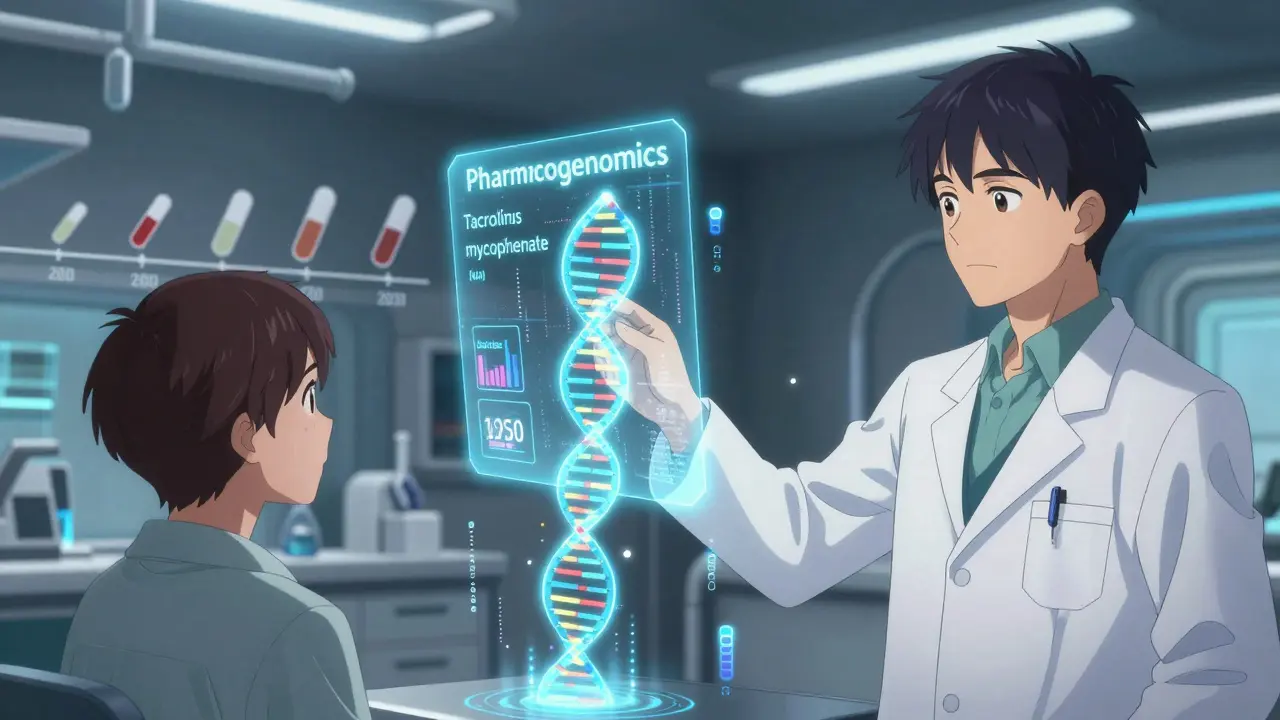

What’s Changing? The Future of Immunosuppression

The future isn’t about more drugs. It’s about smarter, personalized dosing. - Steroid-free regimens are becoming more common, especially for younger patients or those with diabetes risk. - AUC monitoring for tacrolimus and MMF is replacing simple trough levels in top centers. It’s more accurate, but it’s also more expensive and time-consuming. - Pharmacogenomics is starting to play a role. Some people metabolize tacrolimus faster because of their genes. Others absorb MMF poorly. Genetic testing might one day tell your doctor exactly how much you need. - Biomarkers are being studied-blood or urine tests that predict rejection before it happens. If we can catch it early, we might not need to crank up drugs at all. By 2030, experts predict 15-20% fewer people will be on the full triple therapy. Instead, you’ll get a custom plan: maybe tacrolimus and MMF, no steroids, with a new drug added only if needed. It’s not here yet-but it’s coming.What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re on this regimen, here’s what matters most:- Take your pills at the same time every day. Set alarms. Use pill organizers.

- Don’t skip blood tests. Your levels change with diet, illness, and other meds.

- Report diarrhea, fatigue, or mood changes early. Don’t wait until it’s bad.

- Protect your skin. Use SPF 50+ daily, even in winter.

- Ask about steroid tapering. If you’re stable after 3-6 months, your doctor might cut you off.

- Get your flu shot every year. And the pneumonia and COVID vaccines too.

Can I stop taking my immunosuppressants if I feel fine?

No. Stopping these drugs-even if you feel great-can cause your body to reject your new kidney within days or weeks. Many patients who stop taking their meds think they’re cured, but their immune system hasn’t forgotten the transplant. Rejection can happen fast and without warning. Always talk to your transplant team before making any changes.

Why do I need to take tacrolimus and mycophenolate at different times?

Taking them together can increase stomach upset and reduce how well your body absorbs each drug. Spacing them 2-4 hours apart helps your gut handle them better. Your pharmacist or nurse will give you a clear schedule-stick to it.

Do these drugs interact with other medications?

Yes, badly. Proton pump inhibitors (like omeprazole) can lower mycophenolate levels. Antibiotics, antifungals, and even grapefruit juice can raise tacrolimus levels to dangerous levels. Always check with your transplant team before starting any new medicine, supplement, or herbal remedy.

Is it possible to live without steroids after transplant?

Yes, and more patients are doing it. If you’re stable after 3-6 months and have no history of rejection, your doctor may consider removing steroids. This reduces weight gain, diabetes risk, and bone loss. But it’s not for everyone-especially if you’ve had rejection before. Your team will weigh the risks.

What happens if my kidney starts to fail even with these drugs?

Chronic injury-slow scarring of the kidney-can happen even with perfect drug levels. If your kidney function drops, your team will check for rejection, infection, or drug toxicity. They may adjust doses, add a new drug, or consider a second transplant. The goal is to catch problems early before it’s too late.