On January 1, 1995, a global rule changed how the world gets medicine. The TRIPS Agreement - the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights - became law for all 159 members of the World Trade Organization. It forced every country, rich or poor, to grant 20-year patents on pharmaceuticals. That meant no more cheap copies. No more local factories making life-saving drugs at a fraction of the price. For millions in low- and middle-income countries, this wasn’t just a legal shift - it was a death sentence.

What TRIPS Actually Does

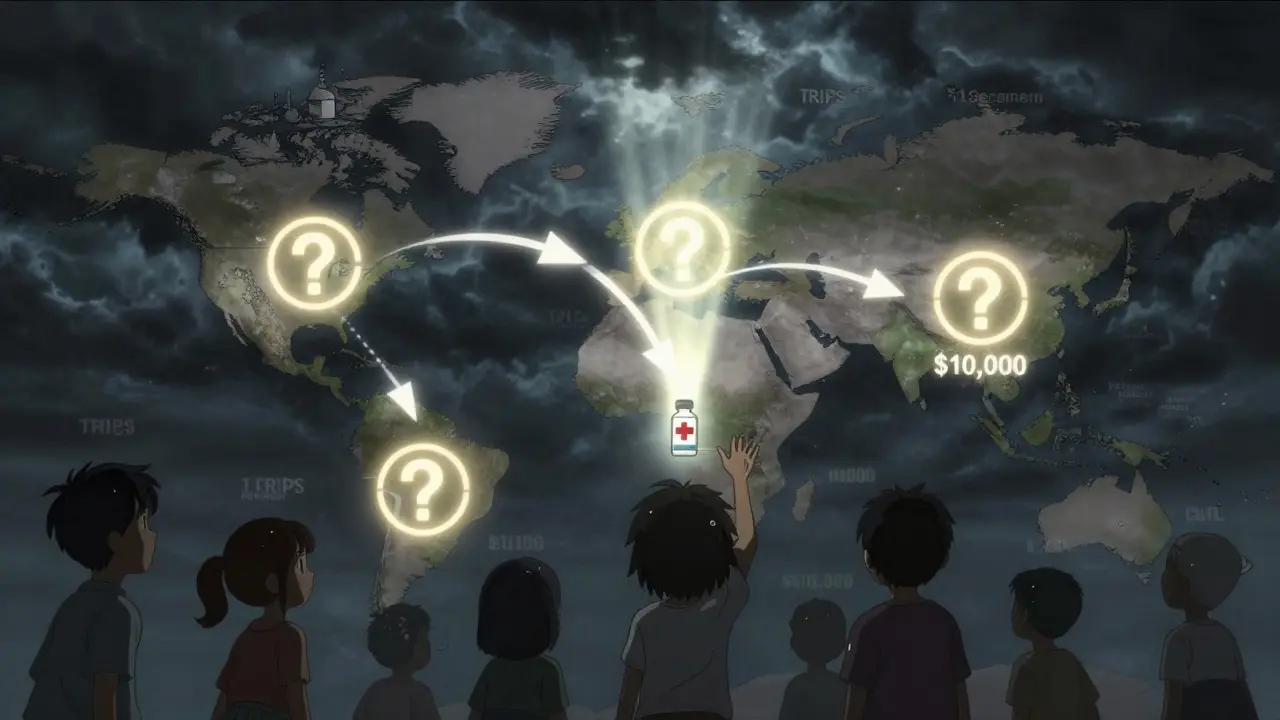

The TRIPS Agreement didn’t invent patents. It standardized them. Before TRIPS, countries like India, Brazil, and Thailand didn’t patent drugs. They made generics. A year’s supply of HIV medicine that cost $10,000 in the U.S. could be bought for $87 in India. That changed overnight when TRIPS came into force. Now, every country had to follow the same rules: patents on drugs, no exceptions, 20 years from filing date. Even if a medicine saved children’s lives, if it was patented, no one could make a cheaper version without permission. The agreement also set strict rules for what counts as a patentable invention. Natural substances? Not patentable. But if you tweak a molecule just enough to make it synthetic? Patent it. That’s how drug companies protected nearly every new medicine - not by inventing something entirely new, but by making tiny changes to existing ones. This is called evergreening. And it kept generics off the market for years longer than necessary.The Flexibilities That Were Never Meant to Be Used

TRIPS wasn’t completely rigid. It had escape hatches - called flexibilities. Article 31 lets countries issue compulsory licenses - meaning they can force a patent holder to let someone else make the drug, even without consent, as long as they pay a fee. Article 31bis, added in 2005, was supposed to help countries that couldn’t make drugs themselves. It let them import generics made under compulsory license from another country. Sounds fair, right? It wasn’t. The process to use these flexibilities was designed to be slow, confusing, and politically dangerous. To import a generic drug under Article 31bis, you had to:- Prove you had no manufacturing capacity

- Notify the WTO 15 days before export

- Get approval from the exporting country

- Pay the patent holder ‘adequate remuneration’ - a term no one agreed on

- Label every pill with the word ‘FOR EXPORT ONLY’

Why Countries Don’t Use Their Own Rights

Thailand used compulsory licenses in 2006 to cut the price of HIV and heart drugs by up to 80%. The U.S. responded by removing Thailand’s trade benefits - costing them $57 million a year in lost exports. Brazil did the same with efavirenz in 2007. The U.S. put Brazil on its ‘Priority Watch List’ for two years. The message was clear: if you use your legal rights, you’ll be punished. A 2017 study of 105 low- and middle-income countries found 83% had never issued a single compulsory license - not because they didn’t need to, but because they were scared. They feared trade wars, sanctions, or losing foreign investment. Even when they had the law on their side, they didn’t have the power to stand up to pharmaceutical giants backed by powerful governments. In South Africa, a 1997 law allowing generic imports triggered a lawsuit from 39 drug companies. The case was dropped only after global protests. That’s not justice. That’s intimidation.

The Real Cost of Patent Monopolies

Patented drugs make up only 12% of prescriptions worldwide. But they account for 68% of global pharmaceutical revenue - $965 billion out of $1.42 trillion in 2022. Meanwhile, 2 billion people still can’t get the medicines they need. In low-income countries, generics make up just 28% of prescriptions. In the U.S., it’s 89%. The same pill, the same active ingredient, the same dosage - but in a poor country, it can cost 1,000 times more. The Medicines Patent Pool, a UN-backed initiative, has helped bring down prices for 44 patented medicines - mostly HIV drugs - in 118 countries. But that’s just 1.2% of all patented medicines. And most licenses are limited to sub-Saharan Africa, even though the same diseases exist in Asia and Latin America. The system isn’t broken because it’s poorly designed. It’s broken because it was designed to protect profits, not lives.TRIPS-Plus: The Hidden Rules That Make Things Worse

Even worse than TRIPS are the ‘TRIPS-plus’ clauses hidden in bilateral trade deals. The U.S.-Jordan Free Trade Agreement, signed in 2001, extended patent terms beyond 20 years. It blocked generic approval until the patent expired - even if the patent was invalid. Similar clauses appear in deals with Colombia, Morocco, and dozens of other countries. A 2021 WTO report found 86% of member states have added TRIPS-plus restrictions through trade agreements. These aren’t accidental. They’re negotiated in secret, often by corporate lawyers, and pushed onto countries with weak bargaining power. The result? An extra 4.7 years of monopoly pricing on average. That’s billions in lost savings - $2.3 billion annually across 34 low- and middle-income countries, according to Health Action International.What Changed With COVID-19?

In October 2020, India and South Africa proposed a temporary waiver of TRIPS for COVID-19 vaccines, tests, and treatments. They argued that during a global emergency, patent rights shouldn’t block access. After two years of pressure, the WTO agreed - but only partially. The waiver, approved in June 2022, covers only vaccines. No diagnostics. No treatments. No future pandemics. It’s a half-measure. And it came too late. By the time the waiver passed, rich countries had hoarded billions of doses. Most low-income countries still hadn’t reached 20% vaccination coverage. The waiver was symbolic. It didn’t fix the system. It just showed how broken it is.

Who’s Winning? Who’s Losing?

The winners are the big pharmaceutical companies. In 2022, the top 10 drugmakers made $312 billion in profit. Their R&D budgets? $170 billion. That’s less than half their profits. Most new drugs aren’t breakthroughs - they’re minor tweaks on old ones. Yet they’re priced like miracles. The losers are the people who need those drugs. In Malawi, a child with HIV still dies because the generic version isn’t available. In Pakistan, a diabetic can’t afford insulin. In Nigeria, a cancer patient waits months for a drug that’s been made cheaply in India for years - but can’t be shipped because of patent rules. The UN High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines put it plainly in 2016: ‘TRIPS has institutionalized inequitable access to medicines.’Is There a Way Forward?

Yes. But it won’t come from the WTO. Countries need to:- Build domestic generic manufacturing capacity - Brazil did it. India still does it.

- Pass laws that ignore TRIPS-plus clauses - if a trade deal violates public health, it should be void.

- Use compulsory licensing aggressively - and publicly. No more quiet negotiations. No more fear.

- Join forces. A coalition of 20 countries issuing licenses together could force prices down faster than any single country.

- Demand a full TRIPS waiver for all health technologies - not just vaccines.

What You Can Do

You don’t need to be a policymaker to make a difference. If you live in a wealthy country:- Ask your government to stop pressuring poor nations over drug access.

- Support organizations like Médecins Sans Frontières, Knowledge Ecology International, and the Access to Medicine Foundation.

- Push for transparency - demand to know which companies are blocking generic production.

- Don’t accept ‘it’s complicated’ as an answer. It’s not complicated. It’s politics.

What is the TRIPS Agreement and why does it matter for generic medicines?

The TRIPS Agreement is a global treaty under the World Trade Organization that requires all member countries to grant 20-year patents on pharmaceuticals. Before TRIPS, countries like India could produce generic versions of drugs at a fraction of the cost. After TRIPS, those generics were blocked unless the patent holder agreed. This directly limited access to life-saving medicines in low-income countries, where people often can’t afford patented drugs.

Can countries still make generic drugs under TRIPS?

Yes, but it’s extremely difficult. TRIPS allows compulsory licensing - where a government can authorize a generic version without the patent holder’s permission. However, the process is legally complex, politically risky, and often met with trade threats. Only one country, Rwanda, has successfully used the international import system (Article 31bis) since 2005 - and it took four years.

Why haven’t more countries used compulsory licensing?

Most countries avoid it because of fear. When Thailand issued licenses for HIV and heart drugs in 2006, the U.S. removed its trade benefits, costing Thailand $57 million a year. Brazil faced similar pressure. Drug companies and powerful governments use economic threats to stop countries from using their legal rights. A 2017 study found 83% of low- and middle-income countries had never issued a single compulsory license - not because they didn’t need to, but because they were afraid of retaliation.

What’s the difference between TRIPS and TRIPS-plus?

TRIPS sets the global minimum standard for drug patents: 20 years. TRIPS-plus refers to stricter rules added through bilateral trade deals - like extending patent terms beyond 20 years, blocking generic approval even after patents expire, or requiring data exclusivity. These are often hidden in trade agreements negotiated by wealthy countries with poorer ones. Over 86% of WTO members now have TRIPS-plus provisions, making access even harder.

Did the COVID-19 vaccine waiver fix the TRIPS problem?

No. The 2022 WTO waiver only covers vaccines - not tests, treatments, or future pandemics. It also has complex conditions, like requiring each country to notify the WTO before producing generics. By the time it was approved, rich countries had already bought most of the world’s supply. The waiver was symbolic. It didn’t change the system - it just proved how slow and broken it is.

How do patent rules affect drug prices globally?

Patents keep prices high. In the U.S., generics make up 89% of prescriptions but only 20% of spending. In low-income countries, generics are only 28% of prescriptions - because they’re often blocked by patents. The same HIV drug that costs $87 a year in India can cost $10,000 in the U.S. That’s a 1,000-fold difference. Patents aren’t about innovation - they’re about monopoly pricing. The top 10 drug companies made $312 billion in profit in 2022, while 2 billion people still can’t access basic medicines.

What’s the future of generic medicine access under TRIPS?

Without major reform, the gap will widen. The UN projects 3.2 billion people will lack access to essential medicines by 2030 if nothing changes. Some progress is happening - like the WHO pushing for TRIPS flexibilities to apply to digital health tools. But real change requires countries to stop fearing retaliation, build local manufacturing, and unite to challenge patent monopolies. The law gives them the tools. They just need the courage to use them.